Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Read online

Page 2

To lend symbolic significance to this study, I have chosen to organize it around the theme of footbinding. Widely practiced in China from the twelfth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, footbinding involved tightly wrapping the feet of young girls with bandages until the arches were broken, the toes permanently bent under toward the heel, and the whole foot compressed to a few inches in length. Despite the excruciating pain that it caused, parents continued to subject their daughters to this crippling custom because bound feet were considered an asset in the marriage market, a sign of gentility and beauty. So difficult was it to walk far unassisted that it also kept women from "wandering," thus reinforcing their cloistered existence and ensuring their chastity.' Although footbinding was not widely practiced in America (only merchant wives who immigrated before 1911, when the new gov ernment in China outlawed footbinding, had bound feet), it is still applicable to this study as a symbol of women's subjugation and subordination. io

Thus, as applied in Chapter 1, "Bound Feet: Chinese Women in the Nineteenth Century," footbinding represents the cloistered lives of most Chinese women in nineteenth-century San Francisco. Whether prostitute, mui tsai, or wife, they were doubly bound by patriarchal control in Chinatown and racism outside. Confined to the domestic sphere and kept subordinate to men, these women led lives in America that were more inhibiting than liberating. In Chapter z, "Unbound Feet: Chinese Immigrant Women, r9oz-192.9," the metaphor is further extended as a measure of social change for Chinese American women. Here we look at Chinese immigrant women's efforts to take advantage of their new circumstances in America to reshape gender roles and relationships-in essence, to unbind their socially restricted lives with the support of Chinese nationalist reformers and Protestant missionary women. Chapter 3, "First Steps: The Second Generation, 19zos," explores attempts by American-born Chinese women to take the first steps toward challenging traditional gender roles at home and racial discrimination in the larger society. While some openly rebelled as flappers, most accommodated the limitations imposed on them by creating their own bicultural identity and lifestyle, although within the parameters of a segregated social existence, and waited for better opportunities. In Chapter 4, "Long Strides: The Great Depression, 1930s," we see how both generations of Chinese women in San Francisco stood more to gain than lose by the depressed economy. Ironically, because of past discrimination, they were able to take long strides toward improving their socioeconomic status, contributing to the sustenance of their families, tackling community issues, and joining the labor movement. Finally, Chapter 5, "In Step: The War Years, 1931-1945," delineates how Chinese women-by joining the armed services, working alongside other Americans in the defense factories, and giving generously of their time, money, and energies to the war effort in both China and the United States-came to fall in step with the rest of their community as well as the larger society.

This outline of the progression of social changes in the lives of Chinese American women is not to suggest that their status moved only in a linear direction, because they did experience setbacks along the way; rather, it suggests that their lives were constantly changing in response to conditions within a specific sociohistorical context. Moreover, although Chinese nationalism, Christianity, and acculturation encouraged resistance to multiple forms of oppression, they also extracted a heavy price from Chinese women, calling on them to put aside feminist concerns for the sake of national unity and to go against their cultural heritage in favor of Western values. In response, Chinese women took the pragmatic course, shifting their behavior as needed to adapt and survive in America. The well-being of their families, community, and country always came first, but that did not mean passing up opportunities along the way to improve their own situation as well. Nor did women easily give up their traditional modes of thought and behavior. Like other immigrant women, mothers chose to continue or change their traditional ways according to what suited their new lives in modern America, while daughters chose to fuse selective aspects of both cultures into a new bicultural identity and lifestyle."

I chose San Francisco, known as Dai Fow (the Big City) to Chinese Americans, as the focal point of this study because it has served as the port of entry for most Chinese immigrants throughout their history. As such, the city has the oldest, and until recently the largest, Chinese population in the United States (now exceeded by New York), as well as the richest depository of archival materials on Chinese American women. It also provides a diverse range of women to interview, many of whom can still recall life for themselves and their mothers in San Francisco during the early i 9oos. Their experiences, of course, are not representative of all Chinese American women, many of whom led very different lives in other urban centers and rural communities during this same time period. But because of San Francisco's significance as an economic, political, and cultural center in Chinese American history, it is an important and logical place to start in documenting the social history of Chinese American women. I hope, though, that this study will inspire further research on Chinese women in other parts of the country where they have also settled.

I settled on the years from 1902 to 1945 as the pivotal period of social change for Chinese women in San Francisco for a number of reasons. The year 19oz marks the first time that the issue of women's emancipation was publicly aired in San Francisco Chinatown. This was done by Sieh King King, an eighteen-year-old student from China and an ardent reformer, who, in a historic speech before a large Chinatown crowd, denounced footbinding and advocated equality between the sexes. The year 1945 marks the end of World War II and the turning point for Chinese American women in terms of improved racial and gender relations and increased socioeconomic opportunities. In between these benchmark years, both immigrant and American-born Chinese women learned to challenge and accommodate race, class, and gender oppression in their lives, to make the most of the socioeconomic opportunities and historical circumstances of this time period, and to define their ethnic identity and broaden their gender role as Chinese American women.

Uncovering and piecing together the history of Chinese American women has not been an easy task. There are few written records to begin with, and what little material does exist on the subject is full of inaccuracies and distortions. Thus, I have had to draw from a unique but rich variety of primary sources: government documents and census data, the archives of Christian and Chinese women's organizations, Chineseand English-language newspapers, oral histories, personal memoirs, and photographs. Taken together, these sources, I believe, provide an alternative and more accurate view of Chinese American women than has existed before, for they show definitively that these women were not passive victims but active agents in the making of their own history. At the same time, I am well aware that these sources are biased, telling us more about the experiences of educated, middle-class women than of illiterate, working-class women; of the American-born than of the immigrant woman; of the exceptional achiever than of the ordinary homemaker. Mindful of this skewed representation, I have tried to compensate by qualifying my descriptions of Chinese women's lives and using oral histories of common, everyday women whenever available.

Government reports and census data, although often biased and inaccurate, provided important quantitative data with which to measure the socioeconomic progress of Chinese American women throughout the period under study. For example, the i goo, 1910, and 19 z.o unpublished manuscript censuses for San Francisco-which list Chinese women as household members, giving their age, marital status, country of birth, year of immigration, literacy, and occupation-helped to create a comparative picture of family structure, the prostitution trade, Chinese women's ability to read and write, and their occupational concentrations. The published census reports for z 94o and 19 50, together with local survey reports by the Community Chest of San Francisco and the California State Relief Administration, provided additional important socioeconomic data for the 1930s and 1940s. The immigration files at the National Archives were invalu

able in helping me trace the immigration experience of my own family as well as that of Chinese immigrant women in general.

Missionary journals and case files from the Presbyterian and Methodist mission homes told harrowing stories about the plight of prostitutes, mui tsai, and abused women who sought the help of Protestant missionaries. On the whole, they gave a general, though oftentimes sensationalized, picture of the oppressed lives of these women as recorded from the perspective of missionaries seeking to rescue and "civilize" them. But individual cases, such as Wong Ah So's story in Chapter z, also described the socioeconomic conditions in China and Chinatown that led to the enslavement and mistreatment of Chinese women, as well as the process by which they were rescued and then "rehabilitated." These records also revealed a spirit of resilience, resistance, and autonomy among those who chose to seek or accept the help and services of the mission homes. In addition, articles written by American-born Chinese women in Christian publications provided insights into the cultural dilemma faced by women of that period.

Digging into the archives of Chinese women's organizations, such as the Chinese YWCA and Square and Circle Club (both of which are still active in San Francisco today), yielded written records of social conditions, activities, and perspectives of Chinese immigrant and Americanborn women. Founded in 1916, the Chinese YWCA was created solely to serve Chinese women in San Francisco. Its records and scrapbooks offered substantial evidence of the extent to which women benefited from the organization's educational programs, social clubs, social services, and community projects. The Square and Circle Club was organized in 1924 by seven American-born Chinese women committed to community service. Its scrapbooks revealed the influence of acculturation on the lives of the second generation. Still another important scrapbook, this one belonging to Sue Ko Lee, a member of the former Chinese Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, provided the workers' view of the first labor strike in which Chinese women participated in large numbers.

San Francisco newspapers, in English as well as Chinese, were crucial sources because they chronicled the activities and documented the views of Chinese American women. From the San Francisco Chronicle and San Francisco Examiner came numerous articles about the changing role of Chinese American women, including ones on Sieh King King's famous speech dealing with women's rights; on Tye Leung Schulze, the first Chinese woman to vote; and on the active participation of women in Chinese nationalist causes. Of the four Chinese daily newspapers in San Francisco during the period under study, the Chung Sai Yat Po (literally, "Chinese American daily newspaper") provided the best coverage on Chinese immigrant women. Its inclusion of women's issues, activities, and occasional writings-untapped until now-provided a rare insider's view of the lives of Chinese American women. In terms of periodicals that addressed the second generation, both the Chinese Digest and the Chinese Press were extremely useful in documenting the views and activities of Chinese women during the Depression and World War II years.

Oral histories, despite the drawbacks of faulty or selective memory and retrospective interpretations, added life and credence to this study, allowing women from the bottom up to tell their own history. Indeed, in the absence of writings by Chinese women, life history narratives offer us the only access to their personal experiences, thoughts, and feelings. I was fortunate to have at my disposal over 3 50 interviews of Chinese American women from the following collections: Chinese Women of America Research Project, Chinese Culture Foundation of San Francisco; History of Chinese Detained on Angel Island Project, Chinese Culture Foundation of San Francisco; Southern California Chinese American Oral History Project, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles; and historian Him Mark Lai's private collection. Another rich source of first-hand accounts was the Survey of Race Relations, an oral history project that includes interviews with over zoo Chinese Americans conducted in the 19zos. These voices ring with an immediacy and truth not found in retrospective interviews.

In addition, I personally contacted and interviewed twenty-six elderly Chinese women and six men, all of whom had lived most of their lives in San Francisco. I wanted to learn from the women themselves what life was like for them in San Francisco during the first half of the twentieth century. From the men I wanted to hear their recollections of family and community life, particularly during the Great Depression and World War II years. Many of the women were related either to me or to acquaintances of mine. Some I had come to know through my job as a public librarian, my previous research for the book Chinese Women of America, and my involvement in the Chinese Historical Society of America. Their ages ranged from sixty to one hundred years old, with the majority in their seventies and eighties at the time of the interviews. Six of the women were first generation; twenty-one were American-born. Among them were seamstresses, clerks, waitresses, housewives, and professionals (teachers, nurses, and politicians). My status as an insider (as a second-generation Chinese American woman born and raised in San Francisco Chinatown) and local historian and writer with a proven track record facilitated access to their life stories. I interviewed most of the women alone in their homes, usually for two hours at a stretch. A few of the interviews required repeated sessions and as much as six hours to complete; five were conducted in the Cantonese dialect. Once trust and rapport had been established and the women understood I was trying to write their history for the next generation as well as to set the historical record straight, I found them quite willing to discuss in detail their life histories and views on race, class, and gender issues. Regardless of their educational background, they were articulate, opinionated, and forthright in their responses to my questions, which I asked in a quasichronological and topological order. In my line of questioning, transcription, translation, editing, and selection of passages to include in this book, I have tried to stay true to the spirit and content of their stories as told to me. When necessary, I have corroborated questionable details in their stories against information from other interviews and whatever documentary evidence was at my disposal. As used in this book, oral histories served as one important source of evidence, attesting to the hopes, fears, struggles, and triumphs of women when faced with limitations as well as opportunities.

Though aware of the illiteracy and silence imposed on most Chinese women, I had still hoped to find primary writings or personal memoirs by Chinese American women. For the 1902-45 period, the only such published work is Jade Snow Wong's Fifth Chinese Daughter, an autobiography about the cultural conflicts of a second-generation Chinese woman growing up in San Francisco Chinatown. « In the process of interviewing my subjects, however, I uncovered the following unpublished writings: two autobiographical essays, one by Lilly King Gee Won about her family's involvement in Dr. Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary movement, the other by Tye Leung Schulze about her escape from an arranged marriage and subsequent marriage to a German American immigration inspector; a manuscript by Dr. Margaret Chung about her life as a physician and volunteer in World War II; an unpublished autobiography by Jane Kwong Lee about her immigration to the United States in 1922 and her subsequent involvement as a community worker in San Francisco Chinatown; and the private letters of Flora Belle Jan, a Chinese American flapper and writer. Together, they represent a significant contribution to the scarce published writings by Chinese American women in the pre-World War II period. It is my intention to have a selection of them published in the near future, along with immigration documents, journalistic articles, and oral histories conducted in conjunction with this book.

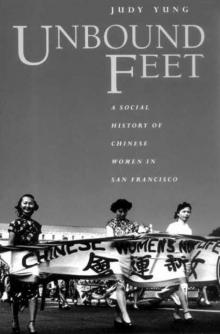

To further embellish the text, I have included photographs from a number of public archives and private collections. Photographs add a rich, visual dimension to this study and provide us with further insight into the hopes and aspirations, immigration and acculturation patterns, family and work life, and social activism of Chinese American women. Moreover, depending on who the photographer was and the circumstances in which the photographs were taken, they also reveal how Chinese American women were viewed by out

siders as opposed to insiders. As a series of images for comparison and contrast, photographs taken at different time periods can also serve as effective markers of social change.

Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco

Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco